Sanitising Imperialism: The Problem of "The Daughters of Kobani"

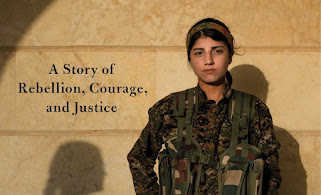

Even before it was released and became a New York Times bestseller, Gayle Tzemach Lemmon’s book The Daughters of Kobani made headlines. In January, it was announced that Hillary Clinton would be co-producing a mini-series on the book alongside her daughter Chelsea, raising eyebrows in some corners, cheers in others, and outright disgust in many more.

The

fact that Clinton, a former Secretary of State and 2016 presidential nominee,

is poised to dip into the world of television to tell the story of the Kurdish

Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) appears at first glance a baffling move. That is

unless one understands that the point of her decision is to present a sanitised

and revisionist version of U.S. policy in Syria, as well as the Middle East

more generally.

Now

that Lemmon’s book has been released to much fanfare, it’s incumbent on those

of us who have been supporters of the Kurdish liberation movement to analyse it

critically, and raise some important questions. Who is Gayle Tzemach Lemmon?

Why is this book being heralded by many in the U.S. foreign policy apparatus as

the definitive account of the YPG and YPJ’s war (and by extension Washington’s

war) on the Islamic State? What is the ultimate aim of the book? Does it do

more good or harm for the cause of the Kurdish liberation movement?

To

tackle the first question, we need to understand that Lemmon is not a neutral

observer, but an active participant. That is to say, she is a writer with a

long track record of doing the bidding of the U.S. imperialist establishment. Lemmon

had written a 2011 Newsweek cover story that touted the role that Hillary

Clinton was allegedly attempting to play globally as some kind of feminist

icon. Furthermore, she is an adjunct fellow at the Council of Foreign

Relations, and even enjoys a role as the CMO of Shield AI, a company

responsible for building drone technology.

Perhaps

even more importantly, Lemmon has been something of an indispensable pen

wielder for the U.S. “war on terror”, writing two other NYT bestsellers Ashley’s

War and The Dressmaker of Khair Khana.

These books largely extoll the alleged virtues of the United States intervening

in Afghanistan in the post 9/11 world, highlighting the role of women in U.S.

Special Operations and an Afghan woman entrepreneur, respectively.

It is in this ideological vain where this book picks up. In the foreword, Lemmon writes that she was approached by a member of U.S. Special Operations who was in Syria in early 2016 about the need to come and see for herself what was taking place there. As she was told, the active participation of women’s fighters on the frontlines of the war against the Islamic State was “unbelievable”. With that, Lemmon couldn’t resist her impulses to witness this women’s revolution.

It must be said that Lemmon is clearly a proficient writer and a talented story teller. She weaves the stories of YPJ fighters and commanders with a great deal of skill, in a way that does certainly seems to do justice to contextualising what their lives were like before ISIS, as well as their indispensable and heroic role on the frontlines. In this regard, the book is an engaging and powerful read.

She also does provide a decent level of historical background on the YPG and YPJ, the Rojava Revolution, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and its leader Abdullah Ocalan, who serves as the ideological inspiration for the Kurdish liberation movement. She even mentions – surprisingly enough – that the U.S. had a role in putting Ocalan in prison when he was captured in Kenya in 1999. Lemmon also provides a historical backdrop on the national oppression of Kurds in Syria that had rendered up to half a million stateless.

However, there are undoubtedly political problems with the book – or perhaps, they are political statements of intent.

It is said that the YPJ and the broader Kurdish Freedom Movement follow a left-leaning ideology, and it is implied that it is because of the ideological turn of the PKK in the mid-2000s from Marxism-Leninism to democratic confederalism that women’s liberation is prioritised. Although it is true that jineologi, or the science of women, has been greatly developed since the PKK abandoned Leninism, the origins of their emphasis on this question precedes this. Women have played a valuable role in the movement since the launch of the armed struggle in 1984, and a central and prioritised role in the movement since the 1990s when a separate women’s army was founded.

Of course, it would likely be too much to expect that a book of this sort would extoll the virtues of communism in women’s emancipation. This leads to another interesting observation, which is the supposed strangeness or uniquenes of the YPJ. Throughout the book, the Americans involved are shocked and moved by the ability of women to play such an equal role with men.

However, the YPJ’s war against the Islamic State is far from the first time women have actively participated in such a way on the battlefield. One can recall that in the Second World War – another time that the U.S. allied with a “red army” -- women snipers of the Soviet Union were putting the U.S. to shame when it came to showing women could equal men on the battlefield. We can recall the participation of women in the Cuban revolution, the women comrades of the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua who picked up arms, or even Mao Zedong’s famous phrase “women hold up half the sky”.

But here’s the tricky bit – in all of those cases aside from the Soviet example, the United States always actively opposed those movements. Hence, maybe it’s not so surprising that an author like Lemmon or American Special Operations Forces would react with such shock at women playing a role like this – they never would have witnessed them on their side anywhere on the planet. Lemmon’s previous books certainly parrot the “Taliban bad, U.S. good” line, but let’s recall that it was the United States that helped bring the Taliban to power in the first place by helping to crush a revolution that was both socialist and feminist (Afghanistan’s Saur Revolution of 1978).

Communism is mentioned again when the book discusses how Ocalan adopted many ideas from the works of American eco-socialist Murray Bookchin. Citing Bookchin’s political journey from the Communist Party USA to libertarian municipalism, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact is mentioned. Lemmon writes that “the pact between Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin was too much for him; he could not be part of a party that aligned itself with fascists.”

This wouldn’t have been such a terrible point to make if the book added more context, given that it’s true that Bookchin left the CPUSA for this reason. But it’s also a fact that at this point in history – even though it has been more than three quarters of a century – many Americans still don’t know that the Soviets did the brunt of the fighting and dying to defeat fascism. The equating of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in this vein does a great deal to deceive people, and to distort history.

Looking at the complexities of the Syrian war, the book makes the error – or maybe the point – of portraying every other actor in the Syrian war as reactionary, bloodthirsty, or criminal. Russia, ISIS, Hezbollah, the Syrian state, and even China are all painted with the same brush. The 2016 liberation of Aleppo is referred to as “a savage, months-long bombing campaign by Russia”. She goes on to say that “each time the United Nations Security Council took up a resolution to speak out against the regime’s violence, Russia and China vetoed it.”

When discussing the U.S. bombing campaign that saw the YPG, YPJ and Syrian Democratic Forces liberate Raqqa, she does mention humanitarian concerns – but civilian casualties are not referred to as the consequence of a “savage” campaign. Similarly, one could certainly make the argument that the U.S. bombing of Mosul in the same year was similarly horrendous. Russia certainly made such points to spite the U.S. in response to their accusations of Aleppo’s violent liberation, which seem sensible enough if we want to avoid lapsing into hypocrisy.

Lemmon’s book also bizarrely doesn’t mention a word about Afrin in the context of the 2018 Turkish-backed occupation of the city by many former members of ISIS who had been rebranded. Perhaps it would have been too embarrassing to point out that the United States was clear from the beginning that it had no desire to aid its supposed “partners” in Afrin (or west of the Euphrates River) – or maybe it was because in that occasion, there was collaboration between the YPG and the Syrian government.

For the rather apolitical American reading the book, it will merely hammer home notions about the supposed “goodness” of U.S. missions in the Middle East. Although Lemmon does mention that the Islamic State has its origins in the U.S. war on Iraq, morphing from al-Qaeda in Iraq into the more brutal version it was to become, there is never a criticism of the U.S. war machine in this regard. Instead, we get empty platitudes about how the 2003 invasion was good for the Kurds in achieving greater autonomy.

It is without a doubt that the role that the United States played through Special Operations forces had a decisive impact on the liberation of Kobani, as well as the subsequent operations in Manbij, Tabqa, and Raqqa that the book captures. For the YPG and YPJ – and more importantly for the Kurdish, Arab, Assyrian, Turkmen and other peoples living in those regions – this was a matter of life and death.

However, never in the book are U.S. geo-strategic interests mentioned, aside from the fact that the Obama administration deemed it necessary to fight ISIS, which is to be taken for granted by the reader. A deeper investigation into the wider interests of the U.S. empire is never brought forward. But again, this would be too much to expect from such a book, which is clearly written to sanitise the grim history of U.S. involvement in the region.

It is unfortunate that the Syrian Democratic Council – the political wing of the SDF – seems to have entertained Lemmon’s book to a great extent. Their office in Washington, D.C. decided to host a book event prior to its launch to celebrate its release. This isn’t just an active collaboration between the SDC and a journalist or writer – it speaks to a deeper strategy of the SDC wanting an entrenched relationship with the U.S., which is clear given the interests Lemmon represents. Whether the SDC realises it or not, the results of moving from tactical military cooperation to any deeper political cooperation can only end in disaster. There can never be true liberation under the auspices of imperialism.

In this regard, it needs to be said rather bluntly: any prolonged involvement of the United States in northern Syria cannot have a positive impact. History has shown that the last thing the U.S. ever wants is for nations to be self-determining, unless those nations decide to stake their future on the side of the empire, in which case they will be subjugated.

The concessions made by the SDC to the U.S. recently (such as the 2020 oil deal with Delta Crescent) are deeply troubling, and run a great risk of putting their entire project on the line. There is no question that Washington has zero interest in supporting any socialist-oriented projects around the world, even if Lemmon or certain U.S. soldiers were amazed by what they witnessed while there.

The Daughters of Kobani is worth reading for the intense and often beautiful stories of YPJ fighters and their will to fight for a society beyond the bounds of capitalism – even if the author somewhat makes a silly comparison in saying they are fighting for an ideology “to the left of Bernie Sanders”. A more acute observer or supporter of the Kurdish liberation movement will know that it is so much deeper than that.

All in all, this official U.S. government-sanctioned account of the war against ISIS in Syria is an engaging read. At the same time, it is one that must be taken in with a vigilant and critical eye, lest we forget that the YPJ and the U.S. are supposed to represent fundamentally opposing and irreconcilable visions for the future.